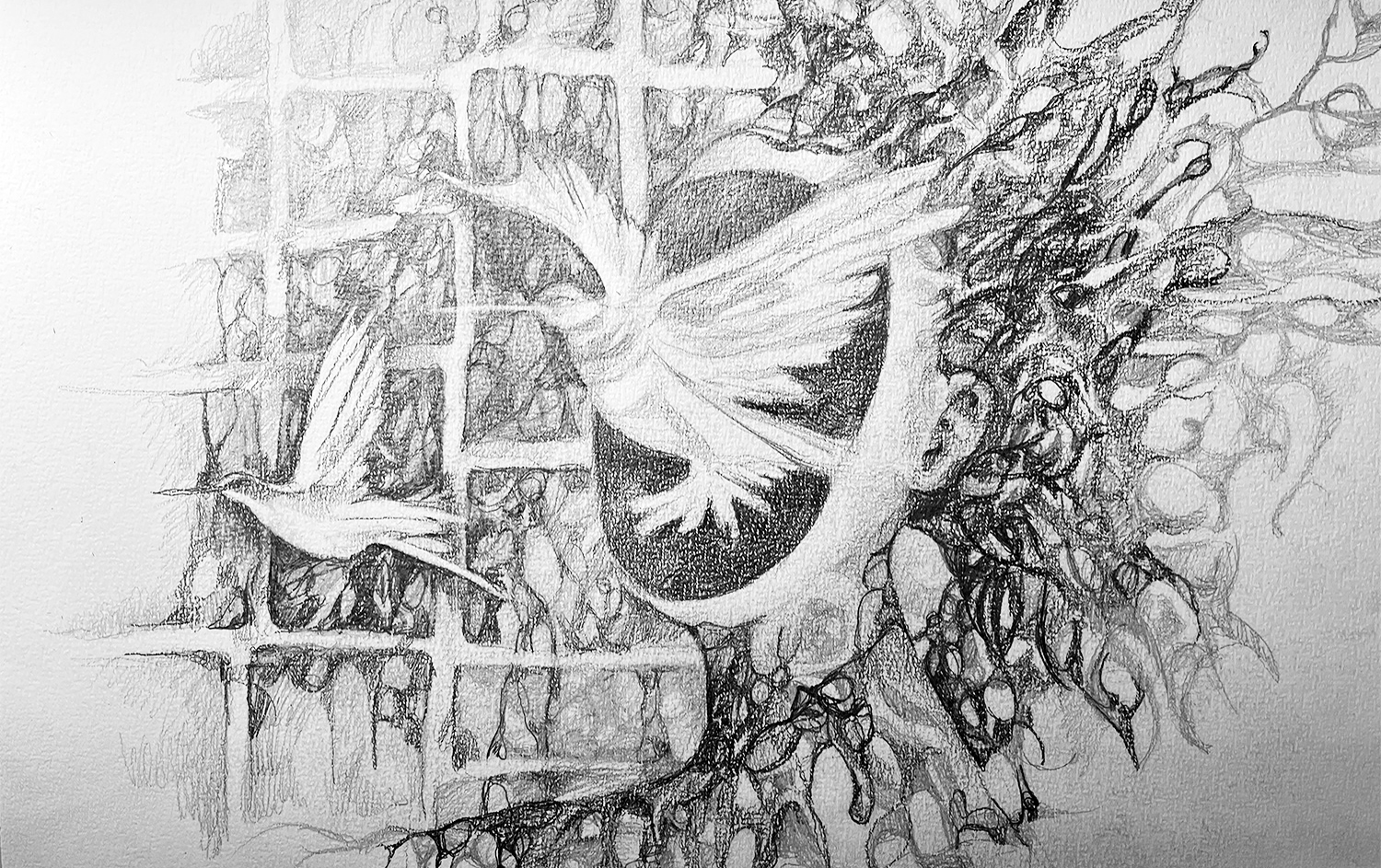

My Grey Zone of Experience: Condolence

By Irina Poleshchuk | Image Irina Poleshchuk

At some point of our life, inevitably, each of us experiences the event of the death of a loved one; a parent, a child, a friend or a life partner.

The death of the other falls on us as a moment of radical alterity, leaving us paralysed and passive. Sometimes we cry for many days and nights, sometimes we are numb with the feeling of a stone weighing down the throat and heart. We prefer dark rooms and isolation, where nobody disturbs us. We switch off mobiles and lock ourselves away from any communication and support, hardly thinking about our closest friends and relatives who are there for us, to help and just to be beside us. We scarcely care about those who are still alive and are with and there for us. People express their condolences, but we barely hear them. There is a tremendous gap between those who are grieving and those who want to express their support and help.

Condolence is a practice of care and sympathy on the occasion of the death of a person’s loved one. What does it mean when we say we offer our “sincere condolences”? Why it is so difficult to find and say the right words? How can I be there for the other person when she is experiencing a traumatic loss of her beloved one? Why do I feel that saying “my sincere condolences” is not enough? Why does the feeling of alienation prevail and dominate me now, almost every day? Why does this shimmering sensation of “not being enough” almost kill us? Surfing the internet, I search for right words for the message. One of many websites – “40 Thoughtful condolence messages to send to family or friends” – proposes alternatives: “Thinking of you during this difficult time”; “You’re not alone. I’m here to be a shoulder to cry on and an ear to listen to anything that you may want to share”; “Losing someone so close is so hard. I will be here to support you at any time and any hour. Sending you so much love”; “I know that grief comes in waves. That’s why I intend to be with you throughout this difficult journey.”¹ All these phrases stay frozen in the air, lacking sensibility and not really expressing “my being there for you.” The words feel dull and senseless.

Trying to express condolence, I am in my grey zone of experience: senseless talking, being useless, not being accepted, and not being allowed to share the grieving process. I am grieving for the one who is still alive; my heart is broken because my voice is not heard. As Racine writes in Bérénice, “Do not give a heart I may not receive.”² My soul leaves my body because my condolence is not enough, and “my being there for you” is not received. I am becoming grey and invisible. I am neither fully there for the beloved one nor fully living my daily life.

‘‘Trying to express condolence, I am in my grey zone of experience: senseless talking, being useless, not being accepted, and not being allowed to share the grieving process.’’

Exploring the practice of giving and receiving, in Being Given Jean-Luc Marion writes that the giving should not come back to the giver: giving “my being here for you,” my empathy, my love and my help should not come back to me, because “the gift is perfectly accomplished when I – the giver – resolve myself to receive it.”³ The real event of the givenness happens when the gift is received by the other person in grief, otherwise the giver is crushed, losing the ground under her feet. Marion writes that the givenness of “being here for” contains a particular saturation which goes beyond the subject. It is an event when the subject does not return anymore to the weight of repetitions of her daily life.

In the Death and Dying Facebook group, a woman explains her experience of grieving together with her daughter who lost her husband:

April 14th was the 14th death anniversary of this young man, my son-in-law, Tommy. He died too young (33), leaving five daughters from the age of 10–2 and my daughter, unexpectedly, found herself a single mom and young widow. I get it. Time heals nothing. Grief is never truly behind you. Life might go on but it is a dim and distant place now. Now I live for us both.

Saying that “now I live for us both,” she shares the grief. Here the giving, i.e. “being there for you” is to take the grief upon oneself. This unaddressed experience, this grey zone of unspoken “I am here” or “I am not enough” at the very moment, becomes shared and saturated with the light of empathy.

The grief never ends completely: from time to time, we look for the signs and traces of those who have gone in birds coming to our windows, in the strange shapes of leaves, in mysterious sunlight and images of clouds. Reflecting about the chronology of grieving, another witness on the same Facebook group writes witness writes:

Grief is not linear. People kept telling me that once this happened or that passed, everything would be better. Some people gave me one year to grieve. They saw grief as a straight line, with a beginning, middle, and end. But it is not linear. It is disjoined. One day you are acting almost like a normal person. You maybe even manage to take a shower. Your clothes match. You think the autumn leaves look pretty or enjoy the sound of snow crunching under your feet. Then a song, a glimpse of something, or maybe even nothing sends you back into the hole of grief. It is not one step forward, two steps back. It is a jumble. It is hours that are all right, and weeks that are not. Or it is good days and bad days. Or it is the weight of sadness making you look different to others, and nothing helps.

Time is still looping, bringing back memories and gaps of “before” and “after,” making any relations with others difficult or even impossible.

When someone is shocked because of the sudden loss of the person closest to them, the first thing is to do nothing. Do not run to her or call her immediately. Take a deep breath, be present in the emptiness of the moment, and tune into all the beauty of this grey experience. Ask yourself: what is happening to me? And what might be happening to her? Feel a grace in being beside someone who is grieving, as the veil between the worlds and between people is pulled back. There is incredible scariness in the space which could divide people but could also bring them closer. And it is a chance to absorb the enormity and inevitability of a grey experience.

¹ “40 Thoughtful condolence messages to send to family or friends” https://www.goodhousekeeping.com/life/a40119939/condolence-messages/.

² Jean Racine. Bérénice. In The Complete Plays of Jean Racine. Vol. 1. Trans. Samuel Solomon. New York: Random House, 1967, p. 426.

³ Jean-Luc Marion Being Given. Towards a Phenomenology of Givenness. Trans. Jeffrey L. Kosky. Stanford University Press, 2012, p. 110.

Leave a Reply