‘One Morning It Had Happened’: On Entering Exceptional Circumstances

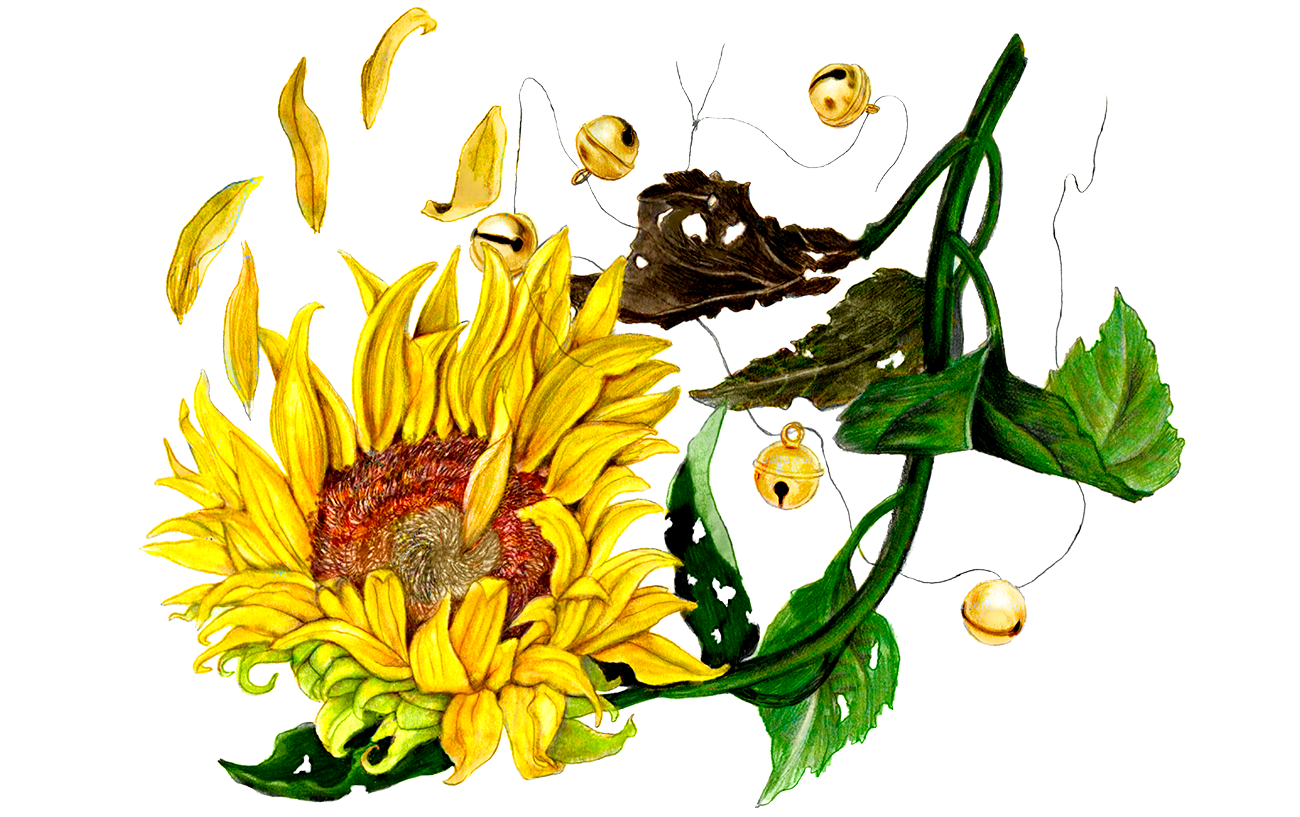

Text Erika Ruonakoski Image Pauliina Mäkelä

Sometimes we just fall into bad times like Alice fell into the rabbit hole: without warning, all of a sudden, headlong. When we are to get back up again, we do not know.

In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Alice follows a white rabbit into a hole, ending up in a drastic fall: ‘The rabbit hole went straight on like a tunnel for some way, and then dipped suddenly down, so suddenly that Alice had not a moment to think about stopping herself before she found herself falling down what seemed to be a very deep well.’

Since Lewis Carroll’s days, ‘going down the rabbit hole’ has become a metaphor for a number of things: the use of psychedelic drugs, sinking into issues of mental health and becoming enthralled by conspiracy theories. The general idea is that the one who has gone down the rabbit hole lives in a parallel reality or a kind of unreality, from which one cannot find a way out.

Over the past few years, we seem to have been sinking deeper and deeper into a world of oddities. We had only just got worried about ‘alternative facts’, the rise of authoritarianism and the acceleration of climate change, when the COVID-19 pandemic turned our lives upside down. As the end of the pandemic was, once again, almost in sight, Vladimir Putin attacked Ukraine, threatening ‘those who interfere’ with nuclear war.

When trying to understand the confusion brought about by sudden crises, it is helpful to read accounts of the onsets of earlier ones. In her memoirs, Agatha Christie describes the beginning of the First World War in an easily recognisable way: ‘When, in far off Serbia, an archduke was assassinated, it seemed such a faraway incident – nothing that concerned us… It was all rumours – people working themselves up and saying it really looked “quite serious” – speeches by politicians. And then suddenly one morning it had happened. England was at war.’

Simone de Beauvoir’s description of the escalation of the Second World War in France proceeds in a similar manner: ‘During the early summer of 1939 I had not yet wholly given up hope. An obstinate voice still whispered inside my head: “It can’t happen to me; not a war, not to me.”’ In September of that year, after Germany’s invasion of Poland, France and the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. In May of 1940, Germany attacked France. ‘Then one morning it happened’, Beauvoir writes about the war becoming a reality and the transfer of her partner to the front.

These accounts highlight the existence of two selves: the pre-war ‘naïve self’, and the self that has witnessed the onset of war. The naïve self tries to hold on to its conception of the world as long as it can. Before the major offensive of Russia on 24 February 2022, many Ukrainians remained calm despite the warnings of the United States. They presumed that the Russian troops mustered in the nearby areas would not attack Ukraine.

When we understand that something horrible can happen and is in fact happening to ourselves or to our loved ones, confusion takes hold. The meaning of action seems to disappear along with the future horizon that used to guarantee that meaning. Against the threat of a pandemic or a war, the innumerable little things that have tied us to our projects start to look trivial. Now all action that is not related to the solving of the crisis seems futile. In this sense, it is easy to understand that so many are willing to sacrifice their lives to defend their country. As for the fight against the pandemic, it has been difficult to find effective ways of action: avoiding get-togethers, washing our hands and wearing a face mask have provided a framework for our lives without giving them meaning.

When compared to the situation in which a war between two countries is going on in Europe, a positive aspect emerges from the earlier pandemic situation: despite everything, most European countries have still been able to provide fundamental security for their citizens. A breach of trust in the continuity of things takes place in the circumstances of pandemic as well as war, but in each case the pain we confront is different. The pandemic-related despair has to do with the persistence of the invisible adversary as well as with its ability to change all individuals into potential carriers of infection. War and its threat refer to a state of total insecurity. Where can we find motivation for our actions when everything could turn to ash in an instant?

Freezing up, however, is useless, especially when the war remains distant. Life must go on; we have to work. Beauvoir describes her life during the Algerian war (1954–1962) as follows:

There were times when I truly lived the horror of that war: when people told me about particularly dreadful episodes, in a chance meeting, when I came across an article in a newspaper. At those times, I was filled with this horror to the point of not imagining that I could think of anything else. But naturally, in the course of the day, I had things to do – I slept, I took walks, the weather was nice – I forgot. And yet the horror was always there. One did not take walks in the same way, the sky was not the same blue it would have been if not for this war. It was on the horizon even when I did not realize it in its horror.

This is how we, too, exist from day to day: glancing continually at the news, yet trying to make everyday life possible by distancing ourselves from the horror, and still, at the back of our minds, remaining aware of the destructiveness and dangers of the ongoing war.

***

‘Down, down, down. Would the fall never come to an end?’ wonders Alice while falling. Ultimately Wonderland is anything but a nice place, and Alice ends up on a collision course with its insanity: the use of reason does not provide security in the face of a warmongering will that twists all logic. ‘Sentence first – verdict afterwards’, says the tyrant. In Through the Looking-Glass, sentences are likewise given according to the principle of ‘living backwards’. ‘He’s in prison now, being punished: and the trial doesn’t even begin till next Wednesday: and of course the crime comes last of all’, says the White Queen, describing the situation of a prisoner.

Like so many other fantasy worlds, Wonderland and the Looking-Glass world can also be interpreted as satirical depictions of the peculiarities and madness of the human world. Alice’s adventures in Wonderland end in a situation in which she questions the tyranny of the Queen and King of Hearts – calls their bluff – and exclaims: ‘Who cares for you? You’re nothing but a pack of cards!’ This is when the whole pack of cards attacks Alice – and she wakes up in an idyll by the riverside, her head in the lap of her sister. ‘Oh, I’ve had such a curious dream’, she says.

The sense of ‘unreal’ which characterises living in the present-day world can make us wish that we too could simply wake up and find ourselves back in the lost idyll. Instead, we continue our lives in a world where the events seem to have got out of hand. Our difficult task is to stay wide awake in the midst of all the insanity and destruction, and still maintain our ability to both act and dream.

Literature

Beauvoir, Simone de. 1984. The Prime of Life. Trans. Peter Green. Harmondsworth: Penguin. (Original text La force de l’âge, 1960.)

— 2011. ‘My Experience as a Writer’, in ‘The Useless mouths’ and Other Literary Writings”, 282–301. Trans. Debbie Mann. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. (Original text “Mon experience d’écrivain”, 1979.)

Carroll, Lewis. The Annotated Alice: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. Ed. Martin Gardner. (Originally published in 1865 and 1871.)

Christie, Agatha. 1977. An Autobiography. London: Collins.

Howe, Will. 2021. ‘“We’re All Mad Here”: The Politics of Alice in Wonderland’, The Witness 21 Jan. 2021.

Ruonakoski, Erika. Forthcoming. “Ajallisuus ja rationaalisuus COVID-19-pandemian vaiheissa: järkytys, välitila ja ‘paluu normaaliin’” (Temporality and rationality in the stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: shock, interspace and ‘return to normal’), Ajatus.

Zuhair Al-Khafaji, Mayada and Yarub Khyoon, Ansam. 2014. ‘The Political Game in Alice Books: Carroll’s Satirical Vision of the Age.’

Leave a Reply