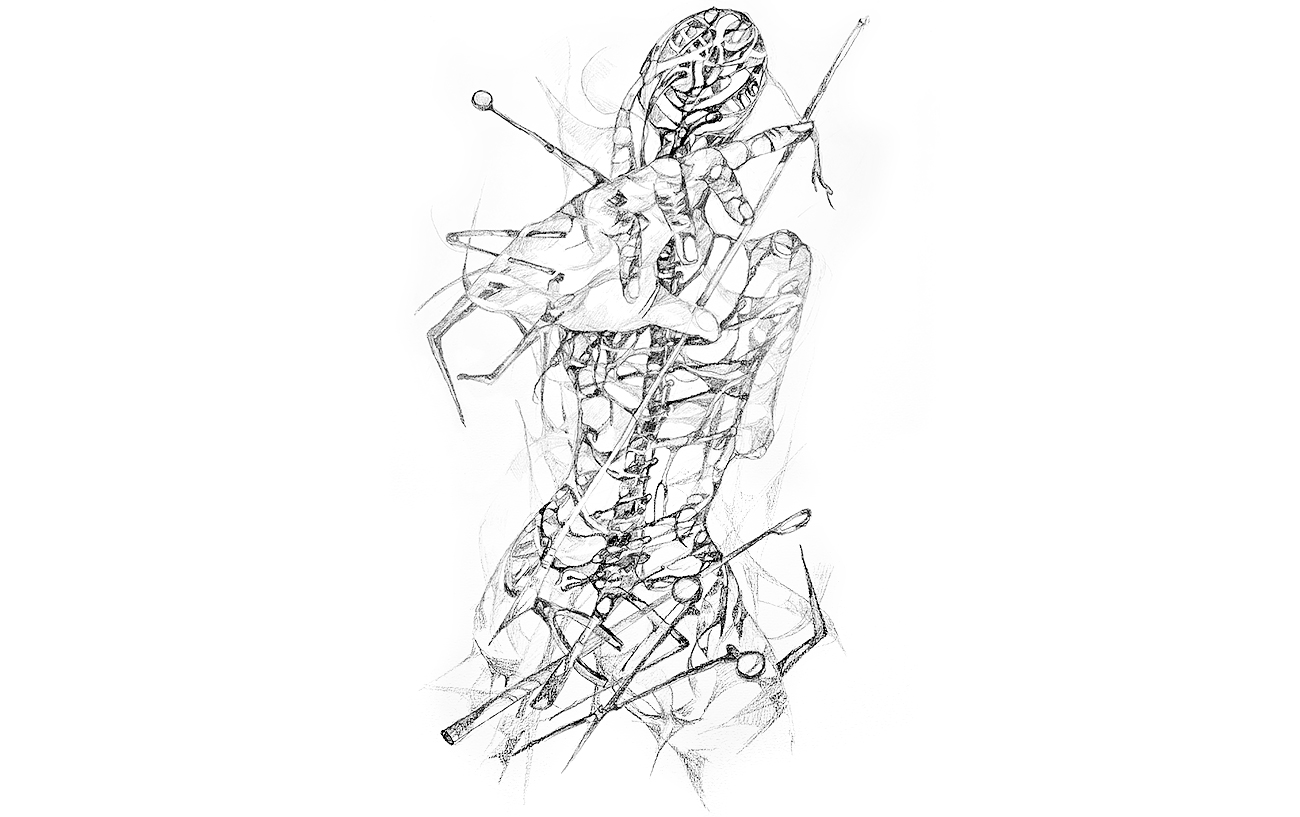

Shame Embodiment

By Irina Poleshchuk | Image Irina Poleshchuk

Stage 1. Pain and shame. How often do we feel that there is something wrong in our body? The strange awareness that the usual normality of how we are in this world is shaken. The sudden pain disrupts the comfort of being and makes us wonder.

I am looking inside my body and trying to detect the alien form in my spinal cord. Some time ago I was diagnosed with a quite big tumour in my back. The immediate effect of these news turns my world upside down: the very first feeling is of being ashamed. I am not normal anymore, I am broken inside, my mind is jumping from one dark scenario of my life to another. I am ashamed of not being enough because of the strong pain in my spine, of not caring enough for my loved ones, of not being efficient at my work, of not being able to walk or to sit. I am ashamed to ask doctors for help again and to demand their attention. I am ashamed because I am not normal anymore in my (physical, social, ethical, sensual, sexual) embodiment. And, what is most shaking of all – I feel death is near again and I am not able to plan for the future.

For some time, I cannot concentrate on anything else than the body-in-pain. More and more the pain in my back creates suffering which subsumes my awareness of the self fully. The acuity of my back pain makes any retreat or escape impossible. As Emmanuel Levinas says, “I am held fast in pain” (Levinas 1981, 52). Talking to the doctor on the phone I realise that it is almost impossible to express in words how it hurts. The pain does not only resist language but deconstructs it. My language is replaced by crying and groaning. The self becomes just pain and nothing else fits in anymore. How easily is my identity shaken? The acute pain makes my body an alien presence, an object other than the usual embodied self oriented towards the world. What I am experiencing together with pain is my visceral body which calls for attention. There is no me anymore in this pain experience because the visceral body appears to me as a strange object.

‘‘ The pain does not only resist language but deconstructs it. My language is replaced by crying and groaning. The self becomes just pain and nothing else fits in anymore. How easily is my identity shaken?’’

My hurt body fills my entire world: each movement brings pain and I constantly feel ashamed of not-being-able. Such negative awareness of my body in pain tends not only to absorb my whole being but it also annihilates intellectual thinking and civilised behaviour. Gradually I realise that my usual unity of mind and body is disrupted and perception, shaken: what I am now with this alien thing in my spine? I am no longer experiencing that I am my body but that I have my body as an object to be treated. At this stage the important conclusion is that my thoughts are not only about my body in pain but also that my reflections are arising from this lived body.

Such back pain not only gives a pre-reflective awareness of discomfort but also of its bodily dimension. I am aware of the pain located in my back even when I am not reflecting thematically upon it. I continue my daily routine with enormous efforts and my pain effects a spatiotemporal construction: I am limited in my movements, and the meaning of space, for instance of my house, is changing. I reorganise my space to avoid places which could affect my pain level, like chairs, benches, putting garbage into bins, and objects being located too low on the shelves. I start to recognise how illness can place us in exile. In this discomfort I feel alienated from things that previously gave meaning to my life: sexual life is almost destroyed, washing hair becomes torture, paddling with my daughter raises anger in me because I can’t trust my body anymore. As Drew Leder expresses it, this is an experience of the distressed body, the body which is pulled a part, losing its wholeness (Leder 2016, 2). In this situation, the sense of the natural world and the way we are bodily present in this world (including consumption, instrumentality, enjoyment of things) are collapsed.

Stage 2. Hospital. Getting ready for surgery. After the diagnosis I go through several appointments in the hospital which prepare me for the surgery. In a medical context, before the surgery, my body does not exist as a physical object of the doctor’s attention but my body and my pain are registered in MRI images, tests and doctor’s statements. I am not examined while being present here in the hospital because my body exists in a digital medical system called Maisa. The doctor looks into the digital system but not at me.

Thus, my ambiguous lived body before feeling pain and my broken mind–body integrity are not of any medical concern. Now, my task is to rewire my relationship with the world while making new meanings for myself through interactions with others and especially here with medical personnel. In terms of phenomenological thinking, the body in pain is not just one thing in the world as an object of medical treatment, but the way in which the new world acquires new meanings (Leder 1990, 25). In this sense, my lived body in pain should become the “here” from which I see the world of far and near, of the present and of the future. The “now” which I interpret is to become a good patient who takes responsibility for my condition, coming to know to treat myself. To be a good patient means to attend to my body as medical professionals might do it, learning to understand my body in a such way that I can recognise different effects of medication and surgery.

From now on, in the hospital I try to use my body experience as a source of information that can help me to care for myself and the nearest future step I am going to take is to get ready for surgery.

The early morning in the hospital is all about routines, heart and blood tests. Another shame experience comes when the nurse asks me to undress fully and to put all my belongings into plastic bags. For some reason this process hurts me because my identity is now kept in plastic bag. This absolute nakedness is reinforced with a special bed in which I am transported to the surgery room. This is about leaving the world and not knowing about coming back, about absolute emptiness in the head without achievements, regrets, plans or moral values. At this moment, in this transportation bed, my being is zeroed. My body in pain, my demanding and exhausting visceral body, is silenced by seven members of medical staff moving around me, examining me, putting in different cables, tubes, directing bright light. I feel the shame of my being zero, of “I don’t care” and of being deprived of all meanings. I have moved from pain embodiment to pure flesh.

These descriptions of experiences are the texts constituted by the ill body and medical work.

Stage 3. After surgery. The pain, and the disruption of one’s previous world that pain results in, make one’s experience as being the other than the self. The pain does not necessarily block but colours the way of engaging with the world and others. The pain never disappears but it can take the shape of another type of pain which paints my being. The sounds of different machines wake me up in intensive care. I am aware that I am still in this world but the body feels like a heavy burden, not mine. Gradually awaking, I am getting back to my sensation, but there is a difference – I cannot build meanings of my existence.

‘‘What meanings emerge out of this disrupted mind–body integrity and of being constantly under the medical gaze?’’

When coming back to life again, the most disturbing question who am I with scars, pain and dizziness? When first scanning my feelings and body sensations, I indicate that I cannot sit or stand up, I am losing gravitation and focus on everyday life activities: it is painful to walk, I can’t run, swim or bicycle. For the third time in my life my body was invaded by instruments and technologies with a skilful doctor’s hands and eyes. I am marked with another big scar and thus, after surgery, my biggest task is how to reclaim my embodiment. This is a painful process of motivating myself and pushing myself back to life. I am ashamed to be weak and I am ashamed to say “I can’t” because my body goes out of control.

One of my conclusions from this phenomenological description is that the event of surgery and different types of pain lead to the loss of the active agency and reinforce the anonymous agency of the medical system which is hyper active, rigorous in monitoring and activating micromanagements of the patient in treatment. What meanings emerge out of this disrupted mind–body integrity and of being constantly under the medical gaze? To heal is to integrate what has been disintegrated. But is it really possible to recreate a body as a consumer and producer? Healing and recovery are not any more the main goals but an endless journey.

Bibliography

Leder, Drew. The Distressed Body. Rethinking Illness, Imprisonment, and Healing. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Leder, Drew. The Absent Body. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Levinas, Emmanuel. Otherwise than Being or Beyond Essence. The Hague, Boston, London: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1981.

Leave a Reply