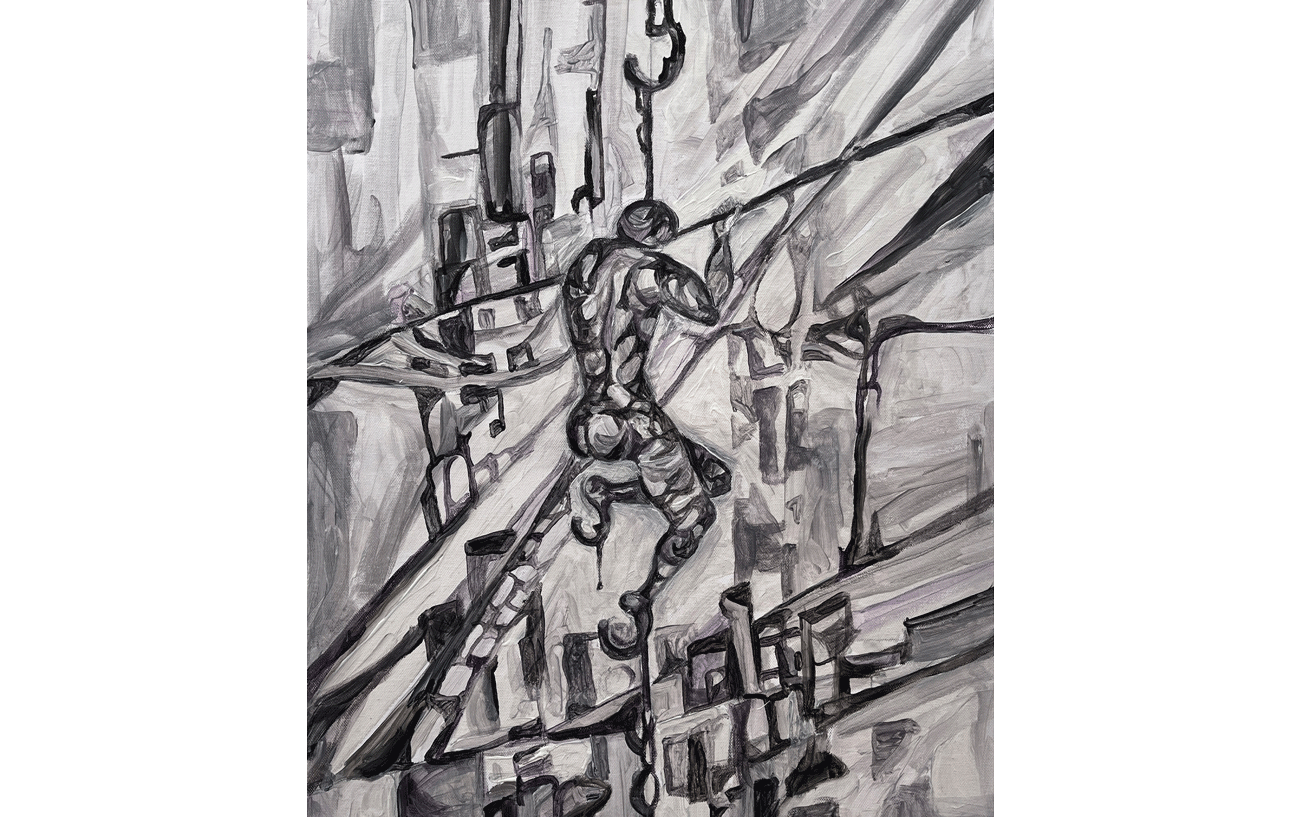

The Outcast: There Is No One to Tell a Story to

By Irina Poleshchuk | Image Irina Poleshchuk

Since early childhood each of us has wanted to tell a story. Coming home from partying with friends, schools, travels, work, we all want to tell or to write a story of events and of overwhelming emotions. All our fresh impressions call for a listener: we chat, we call, we record our messages and send them to our friends and life partners. As we get older, we often dive into our memories to find a good story to share with others and to feel alive again. Stories give symbolic meaning to our personalities and enrich our sensibilities. Sometimes we tell our story in a gentle way, and, sometimes, we shout to get our point across. Stories govern our lives all the way from early age until we die.

There are always two social spheres in our lives. On the one hand we are surrounded by the immediate sphere of family and friends and by our local communities. In a way, we have complete and intimate knowledge of this world, where our words and stories have weight. We are heard and our presence is visible through our stories. Yet on the other, the bigger world is always there, and in this world our personalised stories have no value, none at all. We know very little of this bigger world, and often our voices and actions have no effect. Each of us is balancing between these two worlds: one intimate and close, where the stories are told, and another where we have much less power, and where other stories are imposed on us.

In the news, we can read stories, for instance, about immigrant single parents or just about different foreigners who involuntarily become social outcasts. They have lost their jobs for different reasons such as war and have no income to live on in Finland and to support a child. They are forced to leave Finland, or to move from one country to another one, or to go back to the countries they came from. A single Iraqi father has lost his job and is threatened with deportation, or the father of the family from Russia has lost his business in Finland and now the family is obliged to return to Russia.¹ Some divorced single mothers from countries outside the European Union don’t have financial resources, property, or permanent jobs – there are many cases like these.

‘‘ To be cast out of society is to carry the grief of memories, events, emotions and sensations that are packed into stories and do not find the way out. It is a loss of social space which, for centuries, was carried in stories from one generation to another.’’

Obviously, deportation is a very regular practice of European and non-European states. Having lived in Finland for decades, the people who are deported have gradually lost social and cultural connections with their home countries. Their stories do not belong any more to Iraq, or Russia, or Cuba. In their countries of origin, they are outcasts, since at some point in life they consciously took a decision to dissociate themselves from their native countries and to search for a better life. Curiously, in their homeland, this move can be read as a denial of hospitality. Their stories are heard in neither Finland, nor in any other country where they have lived long enough and now, for different reasons, are forced to leave. Without income and without rights to any social support, these people become double outcasts, rejected by the systems and governments of both countries. Even though they have citizen rights of return to their countries of origin, they will be always be the weird other, the different one, the one “spoiled by the West”. As their compatriots often say: “you don’t know how we live here, so don’t complain”. These outcasts have many stories to tell but they can tell them to no one, because their stories are silenced.

The social outcast is a person repudiated by their community because they are different for many reasons: they do not belong anymore to their homeland, to local societies, their views and behaviour are strange, they are often misunderstood. They can be victimised or bullied, or even they turn into space ghosts, that is, not able to find a place to live, to build up an identity or to tell a story. Their reputation is constantly questioned by their peers, by social rules, and by governments. The outcast is ignored and locked down, deprived of a say and social significance. At some moment in life, for different reasons (missing documents or lack of residence permit, low income, divorce) the outcast fails to fit in with society, and this may contribute to a situation of being isolated in both the country of residence and the country of origin.

Does this situation of being a social outcast remind one of the practice of ostracism in Ancient Greece? Is it an updated version of exclusion in which the state, social systems, or even citizens could vote for the person to be ostracised? While in Ancient Greece the period of being ostracised was reduced to ten years, in contemporary society, it can last much longer.

This could lead to a new form of Japanese hikikomori, self-imposed social withdrawal, a volunteered practice of isolation, an escape from any emotional engagements with other/s and any social participation. Because of a strong social fear, the hikikomori – the modern hermit – is suppressed and it does not move from an intrapsychic space into the intersubjective dimension. To be cast out of society is to carry the grief of memories, events, emotions and sensations that are packed into stories and do not find the way out. It is a loss of social space which, for centuries, was carried in stories from one generation to another. Being an outcast is also being cut off from the ancestral line and from belonging to small histories of local communities.

How many outcasts with unheard stories are there? In Men in Dark Times, Hanna Arendt writes that “the reward of storytelling is to let go”.² Though stories may concern events that seem to have singled a person out, thereby discussing a seemingly isolated and private experience, storytelling will always be a social act of interweaving the past, present and future. Ultimately, to voice the story is to share the world of ethical concern with others.

¹ To mention a few, this article (in Russian) explains new rules imposed on Russians who escaped mobilization in Russia and asked for asylum in Finland “Миграционная служба приостановила предоставление убежища бежавшим от мобилизации Россиянам”; a criminal story is about a man from Saudi Arabia who lost his business in Finland “Обратившийся в фирму по иммиграции мужчина потерял все свои деньги и стал просителем убежища”,

² Hanna Arendt, Men in Dark Times. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973, 99.

Leave a Reply