Agatha Christie and Professor Wanstead’s Opinion

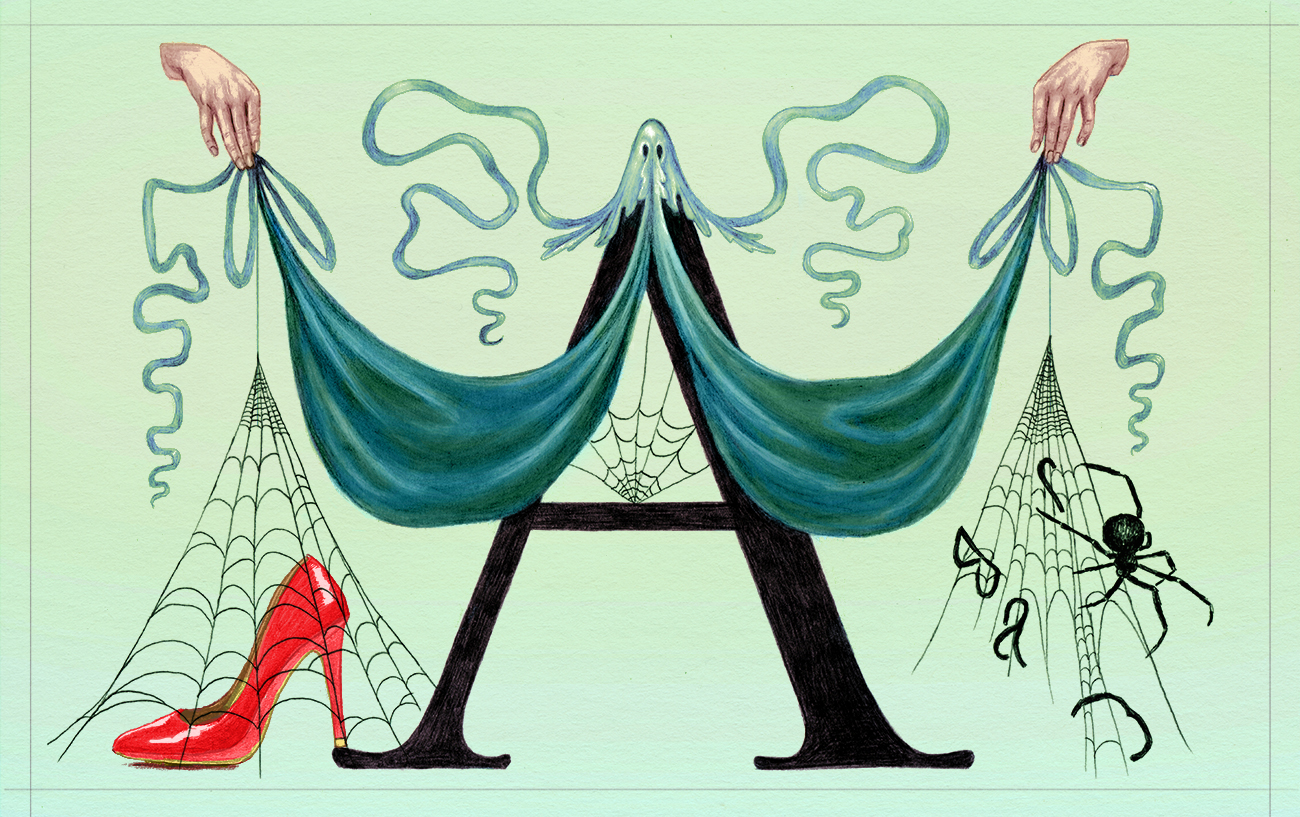

By Erika Ruonakoski | Image Pauliina Mäkelä

In Nemesis, Agatha Christie touches upon the theme of sexual violence in a way that makes some of us regard her as an apologist for sexual violence. What should we think of literature that, in part, betrays attitudes that in our days are considered questionable?

Nemesis (1971) was the last Miss Marple story written by Agatha Christie. The novel deals with the brutal murder of a young woman, and sexual violence possibly experienced by her. One of the characters, Professor Wanstead, says about the case: “Girls, you must remember, are far more ready to be raped nowadays than they used to be. Their mothers insist, very often, that they call it a rape.” Later the same view is uttered by another minor character, Advocate Broadribb: “Well, we all know what rape is nowadays. Mum tells the girl she’s got to accuse the young man of rape even if the young man hasn’t had much chance, with the girl at him all the time to come to house while mum’s away at work, or dad’s gone on holiday. Doesn’t stop badgering him until she’s forced him to sleep with her.”

From the viewpoint of the victims of sexual violence, the problem with these kinds of suggestions is that in them the narrative of the raped women is put into question by default: “rape nowadays”, or, in the case of this murder mystery, in the 1970s, is a lie of a lustful young woman. What kind of attitude, then, should we adopt to Christie’s text? Considering that the supposition of the sexual assault becomes frustrated at the end of the book, should Wandstead’s and Broadribb’s lines be understood as descriptions or even as a mockery of the attitudes of the privileged class?

In Christie’s detective stories, the comic aspect is significant: almost all the characters are presented as somehow ridiculous – and still, in their ridiculousness, human. On the other hand, the questions proposed by some of the characters is a way of keeping readers in a state of uncertainty and generating shifting doubts and guesses in them.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, the function of the opinions expressed in Nemesis remains ambivalent. In a way, the lines of Wanstead and Broadribb are an integral part of the polyphony of the text. Yet they also have the potential to attach themselves to the texture of our broader relationship to the world, either momentarily or more permanently. In that sense, they are not enclosed in the purely fictitious world, apart from the ethically charged challenges of real life. It would be a simplification, however, to read them as the author’s own opinions.

To be sure, Christie’s autobiography reveals that she is like any of us: a child of her times, inclined to accept some of its prejudices and to reject others. The latter tendency can be found in the character of Miss Marple, which questions the reader’s expectations of what a detective character should be as well as what qualities an interesting female character should have. On the other hand, some of the prejudiced views repeated by Christie’s characters over and over again are accepted by Christie herself in her autobiography. The most central one of these is the idea of the heredity of good and bad characteristics: crime is in the genes, and, consequently, beyond “cure”.

‘‘That those who repeatedly confront such prejudices as well as a lack of understanding of the experiential world of their group, criticise stereotypical descriptions, is hardly surprising.’’

In Christie’s detective novels the same idea is expressed in various ways. In Nemesis, Professor Wanstead states: “The misfits are to be pitied, yes, they are to be pitied if I may say so for the genes with which they are born and over which they have no control themselves.” In Ordeal by Innocence, the adopted children remain unavoidably “alien” – they are ticking time bombs, whose genetically inherited features are unleashed despite the good intentions of the adoptive parents.

The same book includes also characterisations, which could, in today’s terms, be with good reason called “racialising” or “sexualising”. A “half-caste” young woman is compared to non-human animals time after time: she is a “dark horse”, “kitten” and “mouse”. In Appointment with Murder (1950), the housemaid Mitzi’s “hysterical” character is likewise explained by her Central European origin. The typification of people according to their ethnic background and bodily features is, however, always made in the dialogue, which makes it possible for Christie to both describe the attitudes of her characters and to lead her readers astray by evoking their own stereotypes. After all, the murderer is hardly ever the foreigner. More often than not, the culprit is a crackpot from the inner circle.

As readers, those of us who escape confronting stereotypical and misleading discussions of our reference groups are in a privileged position. That those who repeatedly confront such prejudices as well as a lack of understanding of the experiential world of their group, criticise stereotypical descriptions, is hardly surprising. It is as if the tacit agreement between the reader and the writer on the intimate co-operation in the charting of worlds would break down in such moments of collision.

On the other hand, literature and other forms of art provide a possibility to at least momentarily embrace realities unlike one’s own, even when they seem alien or repulsive. The practical question we face in the act of reading depends, however, on which group of people we belong to. For some of us the question is: how much foreignness am I ready to confront? For others it is: how much insensitivity and ignorance am I ready to witness?

My research article “Innocence, Deception, and Incarnate Evil in Agatha Christie’s They Do It with Mirrors” (Literature and Aesthetics 2020, vol. 30, no 2, 55–70) also approaches Agatha Christie’s thought from a philosophical perspective. The article includes spoilers from Christie’s novels.

I discuss the communicative aspects of literature in my article “Literature as a Means of Communication: A Beauvoirian Interpretation of an Ancient Greek Poem”, (Sapere Aude vol. 3, no 6, 2012), 250–270 and in Tua Korhonen and Erika Ruonakoski: Human and Animal in Ancient Greece: Empathy and Encounter in Classical Literature, London, I.B.Tauris, 8–41.

Literature

Christie, Agatha. 1950. A Murder is Announced. London: Collins.

— 1958. Ordeal by Innocence. London: Collins.

— 1971. Nemesis. London: Collins.

— 1977. An Autobiography. London: Collins.

Emotion-24.fr

Great content! Keep up the good work!