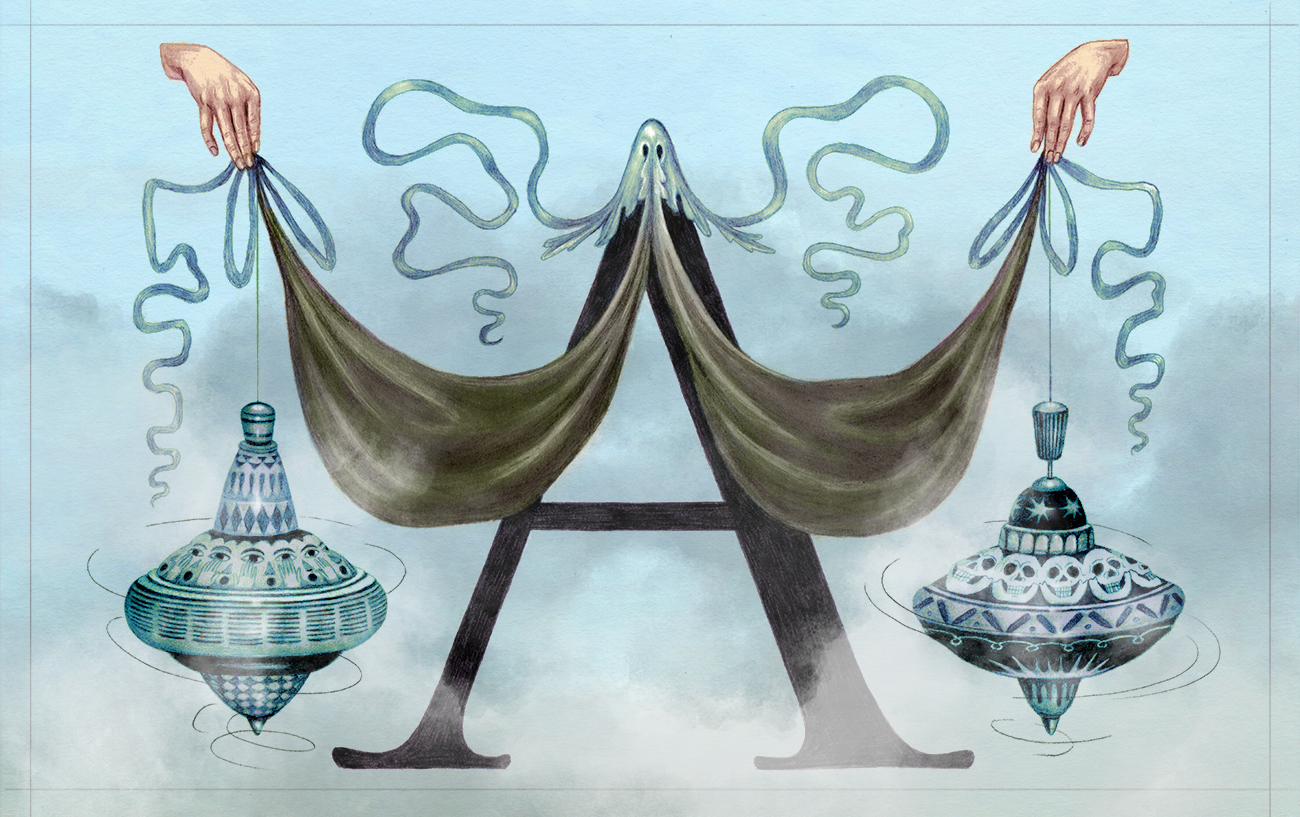

Agatha Christie on Post-Crisis Time

By Erika Ruonakoski | Image Pauliina Mäkelä

In Agatha Christie’s novels There Is a Tide and After the Funeral, the tidal wave of the Second World War has swept across the British Isles leaving behind a bleak landscape: bankrupt businesses, broken families, premature deaths, poverty, rootlessness. When the current tidal waves recede, what will we find?

After the restrictions related to the pandemic have been lifted and it has been announced that we have moved on to an endemic phase of COVID-19, life seems to have got back on track – and yet it has not. It feels like we had been swamped by a tidal wave, and now that it has receded, we cannot really say what has changed. We only have a vague premonition of many of the upcoming changes, and we are not clear about their points of connection with the crisis created by the COVID-19 pandemic, war in Ukraine and climate change.

In Agatha Christie’s detective stories, characters’ lives unfold against the backdrop of collective crises: war is the great destabiliser that throws their lives off track. In After the Funeral (1953) an ex-entrepreneur relates: “the war came and supplies were cut down and the whole thing went bankrupt – a war casualty, that is what I always say”.

In addition to the economic collapse, Christie’s novels refer to the scars left in families when their sons have been killed at the front. She repeatedly discusses the difficulties that those returning from the front have to cope as disabled veterans or adapt again to everyday life. In There is a Tide (1948) one of the protagonists, Lynn Marchmont, who has served in the Women’s Royal Naval Service, finds herself altered by the war:

It was the spiritual danger of learning how much easier life was if you ceased to think… Now, mistress of herself and her life once more, she was appalled at the disinclination of her mind to seize and grapple with her own personal problems.

In a similar manner, the COVID-19 pandemic signified a sudden disruption in life as we knew it. It did not appear as a time of outright instability, however, for “the normal” we longed for seemed preferable precisely because of was more dynamic than the stasis of the pandemic. Yet those living in wealthy conditions can find a point of contact with Lynn’s experiences in how the pandemic gave clear boundaries to life and cut out some choices. This way it may have even eased the anxiety connected to difficulty of choosing and need to keep accomplishing things.

‘‘One day the social, psychological and existential formations left behind by the pandemic will emerge in all their tangibility, like ancient sculptures from dried up lakes.’’

Nevertheless, the constant uncertainty typical of times of crisis produces a specific narrowness of vision: the future is foggy, and one by one, plans crumble. This is what happened when the numerous waves of COVID-19 swept over us, and the people in the midst of war in Ukraine have had to live through this temporal shrinking in a much more severe form. After the Ukrainians had reclaimed the city of Kherson, a young woman described her feelings during the Russian occupation: “We lived here like zombies in fog.”

The post-crisis mental landscape is coloured by a feeling of relief. Even if we have not lived in a country in war, after the removal of the COVID-19 restrictions, we can feel a kind of relief. After the relaxation of the pandemic’s stranglehold, it feels luxurious just to plan your life without the fear that your plans will instantly founder. It feels like freedom.

The crux of the matter may not be that we are factually able to fly to London or to meet our neighbours indoors. It is rather that we can make a choice and believe that what we chose can happen. This is about our relationship to the future: we do not live like zombies in fog, for – up to a point, at least – we can steer our lives.

Nevertheless, whatever is left behind by the pandemic is covered by fog. That something is present, yet hidden. Something surprising has already surfaced: the growing popularity of remote work changes the social life of study and work communities, and possibly makes it more fragile; this reduces the profitability of shops and restaurants and makes organising events more difficult. The technical ease of remote presence chips away at the possibilities of physical nearness.

Are we dealing here with a momentary change? If not, will there be a reaction against this trend? What is lost for good? What remains? One day the social, psychological and existential formations left behind by the pandemic will emerge in all their tangibility, like ancient sculptures from dried up lakes.

Literature

Christie, Agatha. 1948. There Is a Tide. New York, NY: Dell.

— 1953. After the Funeral. London: Collins.

Ruonakoski, Erika. Forthcoming. “Experiential Shifts in the COVID-19 Pandemic: From the Epochē to Interspace and ‘Normality’”, Analysing Darkness and Light: Dystopias and Beyond. Brill.

Saarikoski, Jyrki. 2022. ”Juhlahumua Hersonissa: Ukrainan joukkojen vapauttaman kaupungin asukkaat iloitsevat”, Yle 14/11/2022, accessed 15/11/2022.

Leave a Reply